Thomas Weiss identifies five “gaps” that chronically hamper global governance: knowledge, normative, policy, institutional and compliance (Weiss 2013). In Haiti, those gaps seem to have coalesced into what many Haitians read as an enduring legitimacy deficit. A more charitable interpretation does note instances of UN adaptation – better crime mapping after 2011, a dramatic scaling-up of the Haitian National Police (HNP), and a science-led cholera response – but, examined closely, such achievements tend to appear partial and fragile, leaving the larger breach largely intact.

Knowledge and compliance. MINUSTAH’s 2004 start-up underestimated the dense, shifting alliances between gangs and political patrons. When a contingent from Nepal inadvertently introduced cholera in 2010, infecting more than 800,000 people and claiming over 10,000 lives (Frerichs et al. 2012; Katz 2013), the Organisation spent six years contesting its own liability before an apology was issued (United Nations 2016). Subsequent epidemiological work certainly curbed transmission, yet the delay itself suggested an accountability reflex still subordinate to reputational caution – an impression hard to reverse.

Normative conduct. Sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers, including minors among the victims, seriously undercut the UN’s human-rights narrative. The Associated Press counted more than 2,000 allegations between 2004 and 2016, with very few domestic prosecutions (Associated Press 2017). Reforms adopted in 2017 – victim-centred assistance, mandatory pre-deployment training, a voluntary trust fund – mark welcome movement, and Haiti arguably catalysed those global norms. Even so, the survivors’ experience of limited redress reinforces a perception that institutional learning operates at UN headquarters, not in the quartiers populaires where the harm occurred.

Policy and institutional adaptation. Supporters of the UN strategy point to iterative mandates: from peace enforcement (MINUSTAH) to rule-of-law mentoring (MINUJUSTH) and, since 2019, a slim political office (BINUH), with a Kenyan-led Multinational Security Support force now in train (UN Security Council 2023). Elections held in 2006, 2010 and 2016 proceeded on schedule with heavy UN logistical underwriting, and the HNP expanded from roughly 4,000 officers in 2004 to more than 15,000 by 2020 (Malone and Day 2020). Yet the police have struggled to retain personnel and equipment since the draw-down, and gang territory has again expanded. The pattern suggests that short, mandate-driven cycles may be ill-suited to a state so hollow that capacity must be nurtured for decades, not rotations.

Legitimacy in the balance. Survey data gathered in Port-au-Prince in 2015 found only a minority favouring immediate UN withdrawal, indicating a degree of conditional acceptance; most respondents nonetheless judged the mission “only somewhat” effective (International Crisis Group 2016). Such grudging tolerance implies utility rather than genuine confidence. In other words, the Organisation remains necessary but is seldom trusted.

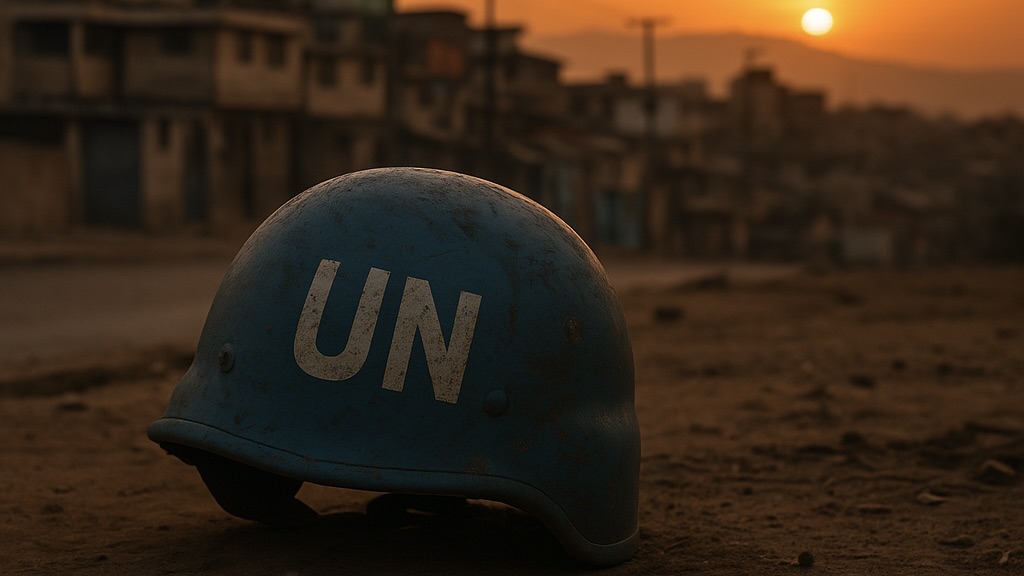

Taken together, Haiti illustrates how partial advances in knowledge production, normative reform, and institutional design, whilst real, have not yet outweighed the reputational cost of early missteps and uneven compliance. Unless the UN sustains a far longer horizon of engagement – accepting that legitimacy is rebuilt in increments and measured locally – its blue helmet risks settling into an increasingly tarnished emblem: credible enough to be tolerated, rarely persuasive enough to inspire.

Bibliography

Associated Press. 2017. “UN Child Sex Ring Left Victims but No Arrests.” Associated Press investigative report, 12 April.

Frerichs, R. R., et al. 2012. “Nepalese Origin of Cholera Outbreak in Haiti.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (47): 19944–19949.

International Crisis Group. 2016. Haiti: Security and the Reinforcement of the Rule of Law. Latin America/Caribbean Report No. 62. Brussels: ICG.

Katz, Jonathan M. 2013. The Big Truck That Went By: How the World Came to Save Haiti and Left Behind a Disaster. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Malone, David M., and Adam Day. 2020. “Taking Measure of the UN’s Legacy at Seventy-Five.” Ethics & International Affairs 34 (3): 285–295.

United Nations. 2016. “Secretary-General’s Remarks to the General Assembly on a New Approach to Cholera in Haiti.” UN Doc. A/71/620, 1 December. New York: United Nations.

United Nations Security Council. 2023. Resolution 2699 (2023) on Haiti. UN Doc. S/RES/2699, 2 October.

Weiss, Thomas G. 2013. Global Governance: Why? What? Whither? Cambridge: Polity Press.